Thank you for coming back to my blog site. In case you have missed any of the previous eight blogs on the Ten Reasons for the Current Heroin Epidemic, please do scroll down to check them out. Today we will be discussing how Mental Health Treatment or actually the lack thereof has contributed to the overall increase in illicit drug and alcohol use, and opiate/heroin dependency.

It is well documented that patients with mental illness are still greatly underserved, and despite some positive movement to increase treatment funding and access, the drastic cuts from the distant and recent past have not been eliminated. NAMI, the National Alliance on Mental Illness, released the report State Mental Health Cuts: A National Crisis which documented the drastic cuts implemented by states between 2009 and 2011 for spending for children and adults living with serious mental illness. These cuts led to significant reductions in community and hospital based mental health services, with a direct effect also on access to psychiatric medications and crisis services. The Medicaid funding issue is a complex analysis, but there is no question that too many patients are left without viable treatment options. In an article by the Pew Charitable Trusts, Some States Retreat on Mental Health Funding, Medicaid expansion “may also have persuaded some states to pull back funding for community mental health centers and other mental health initiatives, including school and substance abuse programs.”

The lack of access is not limited to the Medicaid insured population, as many commercial insurers also do not cover mental health services in parity with medical and surgical illnesses. In addition to private insurance companies not abiding by parity laws, the federal and state governments, who are responsible for overseeing compliance, apparently are not doing a good job, Despite Laws, Mental Health Coverage Often Falls Short. It was also reported that “NAMI found that patients seeking mental health services from private insurers were denied coverage at a rate double that of those seeking medical services … [and] patients encountered more barriers in getting psychiatric and substance use medications.”

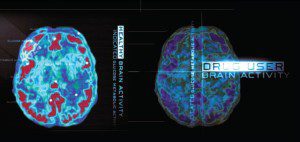

Enough with the statistics! How does this lead to the heroin epidemic? Simply stated, patients with mental illness are no different than patients with a wide variety of complaints – they all want to feel better. However, when there are roadblocks related to funding and access to treatment and medication for psychiatric illnesses, patients look elsewhere to feel better. It is a well-known phenomenon that patients who cannot access care are more likely to self-medicate. So it should not surprise us that patients with depression, anxiety, bipolar illness and other psychiatric health issues reach for drugs that make them feel better: alcohol, stimulants such as cocaine, and opioids such as OxyContin or heroin are commonly used.

When I started this blog series, I promised that I would not only assign blame for the Heroin Epidemic, but also offer solutions. So here is another solution: Federal and State Governments must enforce parity laws and we must increase access and funding for mental illness. As they say in the Midas commercial, “You can pay now or you can pay later, but you are going to pay.” Inadequate mental health treatment can lead to substance use, crime, dysfunctional family dynamics and an overall increase in financial costs to society.

Bad things can happen when mental illness goes untreated, and especially when drug use compounds the situation. In Addiction On Trial this is illustrated by Aunt Betty’s conversation with Jimmy’s father:

Adam continued, “Jimmy’s in jail. He was arrested for possession of drugs. But now they are trying to pin a murder on him, but there’s no proof, and well, it’s really a case of mistaken identity.” Adam tried to ground his runaway emotions, but with a trembling tone he blurted out what he so desperately wanted to believe. “Jimmy had nothing to do with it!”

Adam’s anxious moment gave Betty the opening she needed. “Adam, how can I help? And don’t lie to me. We both know that just because Jimmy may not have intended to do anything bad, well, you know what I am saying. When people are high on drugs, accidents happen and sometimes it looks like it wasn’t an accident.”

And during the trial, Venla Hujanen, the Finnish born District Attorney, also focuses on drugs and mental illness while cross examining Dr. Saul Tolson:

Dr. Tolson spoke softly while nodding affirmatively. The District Attorney proceeded, “So Dr. Tolson, it sounds like you do agree that if a person is addicted to drugs—even though he may have been ‘clean’ for a while, and even though when not using drugs he is able to process things better—if he returns to drug use and again becomes ‘high,’ his anger can resurface, poor choices can be made, and bad things can happen.”

I have included below a copy of the personal letter I received. I look forward to assisting the Surgeon General in his mission to destigmatize the disease of addiction! Remember - "It Takes a Village" and "A Thousand Points of Light".

I have included below a copy of the personal letter I received. I look forward to assisting the Surgeon General in his mission to destigmatize the disease of addiction! Remember - "It Takes a Village" and "A Thousand Points of Light".