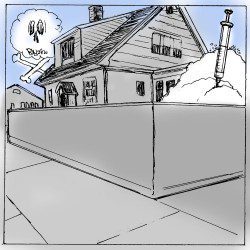

I hope you enjoy meeting Dr. Saul Tolson. At the time of this therapeutic session, Jimmy had been "clean" from heroin for thirty-four months. This would be one of his final sessions with Dr. Tolson before moving from Kansas City to Downeast Maine, where Jimmy would be accused of murder. Read on and experience the life of an addict, who struggles with his past demons; and meet Saul Tolson, the compassionate and insightful therapist, and listen to one of his passionate lectures on the disease of addiction.

Addiction on Trial: Tragedy in Downeast Maine; Chapter 13.

It was the end of March when Jimmy finalized his plans to return to West Haven Harbor. His last three sessions with his Kansas City therapist, Dr. Saul Tolson, were dedicated entirely to the courageous steps and the inherent risks of changing his habitat and job. They reviewed the triggers to drug use and the need for continued awareness that drug addiction is a chronic disease, a lifelong challenge.

Jimmy had heard all of this before but no longer exhibited a defensive response to the message. He was full of optimism. After more than twenty years of drug abuse and addiction, three years at an alternative high school focused on building self-esteem, multiple rehab experiences, and a near death experience, he felt he finally understood the pressures and cues that had guided, or misguided, him all these years. Jimmy had finally acknowledged and fully embraced the message that he could not blame his actions, his addiction, on others. He, and only he, must be accountable for his behavior. He acknowledged and accepted the Twelve Steps of Narcotics Anonymous, a self-help program modeled after Alcoholics Anonymous. Although he could not relate to what he considered to be the subliminal religious connotations of NA or AA, he did ascribe to the message that he needed to admit that which he had no control over and do his best to stay abstinent from drugs and alcohol.

As a member of a program of rigorous honesty, it was problematic to conceal that he was taking a prescribed replacement medication like methadone. He was not alone, as other participants withheld information about medications prescribed by their doctors to treat symptoms and manifestations of illnesses related to the disease of addiction. Many individuals become addicted after turning to either illicit drugs and/or illegally obtained prescription medications in an attempt to self-medicate a primary brain disorder such as depression, anxiety, or bipolar disease. The diagnosis of underlying mental illness can be more difficult to determine for those with the disease of addiction, but many participants in NA and AA do benefit from prescribed medications, some of which have value in the detoxification from drugs and alcohol. Even though many NA and AA groups discourage the use of some prescribed medications that may have effects on the mind, believing that a medication-free approach is always best, most physicians and many Twelve-Step followers disagree with this philosophy.

Jimmy learned through NA and counseling that he could no longer use as excuses the pressure he felt from his father’s professional success or the abandonment by his mother due to her premature and tragic death when he was barely three years old. It had taken him over thirty years to be able to talk about the “what ifs.” What if his mother, had lived? What if she had not left the house that evening to check on an elderly neighbor when the electricity failed? Why couldn’t her friend, Marjorie, have gone instead? These were questions he would never be able to answer, but he was finally able to forgive her and to stop blaming himself for her death. He finally felt at peace with his mother and thought about her daily. He kept her picture in his wallet. He was no longer angry; sadness replaced that destructive emotion. How could he be angry with his mother; she had been so thoughtful and caring in her actions that evening. He was so proud of her and whenever he looked at her photo he could feel her warm eyes looking back at him. He desperately wanted her to be proud of him.

“Jimmy, are you okay?” inquired Dr. Tolson in one of their last sessions.

“Ahh, yes, I was just thinking.”

“I knew that, but what about? It must have been important. You were scratching again at your hand.”

“Yes, I know. When you asked me if I had fully given up my anger and was ready for this transition, I started thinking again about my mother. I really am not angry anymore, but I’ll always wish I could have gotten to know her better. It still hurts that I have no real memory of her when she was alive.”

Dr. Tolson, whom Jimmy called Saul, let silence rule the moment. In his mid-sixties, about the age of Jimmy’s dad, his wiry body was clothed in blue jeans and cowboy boots. He had planned to retire after giving up his private practice of psychotherapy five years earlier and saying good-bye to his many neurotic middle-aged clients. But after two years of retirement he became restless and took his PhD in Psychology into a different arena, first as a part-time consultant and then as a full-time drug counselor at NewBeginningsAddictionCenter. He had never enjoyed work more. The fact that he could trade in his sport coat and tie for more relaxed attire was not an insignificant aspect to the enjoyment he felt while working in his retirement years. Seasoned, articulate, insightful, and with a professional demeanor and attitude of refined independence, he had mentored many young therapists throughout his professional life, and more recently at New Beginnings. But his greatest contribution was to his own patients. He preferred the word “patient” to “client.” This was not a practice of suburban psychotherapy; this was the psychotherapeutic arm for the treatment of a chronic disease and Jimmy was a patient.

Dr. Tolson understood in a very philosophical manner that Jimmy’s illness, the disease of addiction, was composed of biological, psychological, and social elements. He would give lectures on a regular basis to fellow drug counselors, local school committees, police, and to anyone who would listen. He always started his presentation the same way, with a story about the Harvard crew team.

“When I was at Harvard, more years ago than I wish to remember, I was initially confused about why the crew coach recruited athletes who had no prior rowing experience to try out for the scull team. The coach preferred to train disillusioned or frustrated former football players or other passionate athletes who were not quite talented enough to play their chosen sport at the college level. He wanted to teach these athletes how to row from scratch and to learn his way. He was of the philosophy that it is more difficult to undo a wrong technique than to teach the unindoctrinated the correct method. This strategy seemed to work as the Harvard scull teams were always competitive, even at the Olympic level.”

He continued his presentation with a comparison between the approach of the Harvard crew coach and his own current predicament.

“Well, I do not have the luxury of the Harvard crew coach. Everyone in this room already has an opinion of what an addict is. Usually we use the word addict in a special way—cocaine addict, heroin addict, but rarely do we hear the words alcohol addict or nicotine addict. No one would refer to Vice President Cheney as an addict, despite the fact that we know that nicotine contributes to heart disease. And Mickey Mantle remains a hero despite needing a liver transplant because of liver cancer, complicated by cirrhosis from his years of drinking. I am hopeful that each of you can put aside any bias, any preconceived notions that you bring here today. For thirty minutes I ask that you be like that athlete who has never rowed before and put aside your current opinion of addiction. Give me your cleansed minds for just a brief time. At the end of my presentation you may accept, reject, or modify anything I say, but please start now with a clean slate. Before I begin, I want everyone to join me and tightly close your eyes. For just sixty seconds let us each listen to our own breathing and contemplate nothing.”

Not everyone followed Dr. Tolson’s request, some dumping him into the category of one of those earthy crunchy granola type liberals—precisely the type of labeling he was trying to combat, which is why he would wear a sport coat and tie to the lectures. He would wait a full sixty seconds before saying “Now, slowly open your eyes and without verbally responding, I want you each to ask yourself if the last sixty seconds were spent only listening to your breathing while repressing all thoughts. If you were not successful in completely voiding your mind, you now know the struggles of addiction. It is not just mind over matter. I will do my best to further explain the complexities of addiction.”

Dr. Tolson had a sincere and disarming manner to his presentation. Part professor, part psychotherapist, part scientist, but always human, he discussed in painstaking detail the disease of addiction in a respectful manner while laying out the cornerstones of the disease as a bio-psycho-social illness of lifetime duration. He described it as a disease of incurable nature, possible to be put into remission, similar to some cancers. He elucidated the Scandinavian alcohol studies of identical twins being adopted by different families to illustrate that genetic predisposition as well as Skinner-like conditioning were contributing factors. He explained how veterans who had become heroin-addicted in Vietnam could more easily overcome their drug use when returning stateside as representative of the social aspect of the disease; that the elimination of social cues was such a powerful determinant of remission. But the next eye-opening part of his lecture was the presentation of slides showing the reward centers of the brain. He only spent about two minutes on these projections, but it was compelling information.

“I now wish to briefly bring your attention to these next few slides. Here is the nucleus acumbens, the ventral tegmental area, and the prefrontal cortex. They all are integrated into the activation of the brain’s reward pathway.”

Saul Tolson knew all this scientific mumbo jumbo lulled much of the audience to sleep, but he needed everyone to be alert for his next comment. He purposefully lowered the octaves and raised the volume of his voice while adding brief pauses to summon attention as he continued.

“Now, for those of you who have dozed off . . . and I do understand why . . . this next slide is a must to see. It clearly demonstrates that there is very little disparity between the different chemical addictions. This colorful slide demarcates the areas of the brain affected by various drugs and clearly illustrates that alcohol, nicotine, cocaine, and heroin all create their effects through the same common pathway, which originates directly or indirectly at the level of the nucleus acumbens. In fact, the same medication, called naltrexone, is used to curb the craving effects of both alcohol and heroin.”

Dr. Tolson concluded his medical presentation with a sobering analogy.

“Diabetes is a chronic disease. It is a disease that can be controlled, but, as of yet, cannot be cured. It has a genetic component but is exacerbated by poor diet, lack of exercise, and lack of attention to medical management. Think about a person with uncontrolled diabetes or for that matter a smoker with heart disease who eats a bag of potato chips on Super Bowl Sunday and goes into congestive heart failure. Both of these patients now need emergency care that doctors immediately render. Many of these patients return again and again, and for many it is for reasons at least partially due to their noncompliance with recommended treatment. Nevertheless they are readily evaluated and treated for both their acute and ongoing illnesses, even though their own behaviors are contributing or causative factors to their deteriorating health.”

Pausing while attempting to make eye contact with each and every individual in the audience before proceeding, Dr. Tolson delivered his next few lines in a compassionate tone. “With no disrespect, but as a way to reinforce the point I am trying to make, I’d like to ask you to please tell me the difference between a nicotine or alcohol addict, who in some cases may even receive a heart or liver transplant, and someone addicted to heroin or cocaine? Why are those afflicted with the disease of addiction to certain drugs treated so differently than patients who suffer from nicotine or alcohol addiction or other chronic diseases like diabetes? Are they really any different?”

Dr. Tolson never relinquished the podium without one last attempt to convert the naysayers. “Now for those of you who fail to agree with me, and I know you’re out there, let me appeal to your wallets. To incarcerate one addicted patient—that’s right, jailing patients—costs between $40,000 and $50,000 per year. A one-year stay for a patient in a halfway house costs society about $20,000 per year and this does not include any medical care. But to treat one heroin addict as an outpatient with regular individual and/or group counseling sessions, ongoing urine drug testing to monitor for illicit drug use, a complete admission physical exam including laboratory tests that screen for contagious diseases such as Hepatitis C and HIV, and the daily monitoring of medication administration costs approximately $5,000 per year! That’s right—only $5,000 per year or about one-tenth the cost of putting this patient in jail! And how much does it cost and what is the risk to society when patients are denied access to care and get sick with HIV and spread that disease? So what’s the total economic cost of drug abuse to society? You better be sitting down, because according to a ten-year study from 1992 to 2002 on the economic costs of drug abuse by the Executive Office of the President for National Drug Control Policy, the financial price tag to society related to crime, health care, and lost worker productivity is 182 billion dollars—yes, you heard me correctly—182 BILLION dollars! Is not an ounce of prevention worth a pound of cure? Like they say in the Midas commercial, ‘you can pay now or you can pay later, but you’re gonna pay.’ Thank you all for your attention. I am able to stay for questions.”

Uncomfortable with the inevitable applause, Dr. Tolson kept repeating through the clapping, “So, there must be some questions.” The questions came, but none of his answers carried the consequences of those he would have to give to questions posed while under oath at the murder trial of James Frederick Sedgwick in Downeast Maine.