I am honored to have Geoff Kane, MD, MPH as a guest blogger this week.

I have known Geoff for many years and he is not only an extremely competent physician, but also possesses the highest degree of compassion for patients and the utmost commitment to assisting those afflicted with the disease of addiction. Dr. Kane is the Chief of Addiction Services at the Brattleboro Retreat in Brattleboro, VT. He is board Certified in Addiction Medicine and Internal Medicine, a Fellow of the American Society of Addiction Medicine, and Chairs the Medical-Scientific Committee of the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence.

If you want to learn more about Dr. Kane, please visit: geoffkane.com

Thank you Geoff for permitting me to post your insightful and thought provoking blog, which was also posted by the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence, Inc. (“NCADD”).

Curbing Addiction Is Everybody’s Business

By Geoff Kane, MD, MPH

Addiction statistics are scary. For example, excessive alcohol causes an estimated 88,000 deaths per year in the United States. Deaths from cigarette smoke exceed 480,000 per year. In 2013, about 100 Americans per day died from drug overdoses. The annual cost to this country of addiction and other substance abuse—including healthcare, crime, and lost productivity—is over $600 billion.

Such damage ought to prompt interventions that are swift and sure, but that is not the case. Not only have severe social and economic consequences of addiction been with us for a long time; some measures are getting worse.

Conflicts of interest impede the prevention and treatment of addiction by inhibiting individuals throughout society from adopting alternative actions that would reduce the toll of addiction. If we attribute all responsibility for addiction to addicted persons themselves, we are like a naïve family member who says, “It’s your problem. Take care of it.”

People in all walks of life contribute to the proliferation of addiction—whether they realize it or not. The clearest conflict of interest, however, may indeed lie within the individual with addiction. More addictive substance will surely forestall withdrawal and ease emotional and physical distress, and perhaps cause pleasure as well. In the “logic” of addiction, competing priorities such as family, career, and citizenship are eclipsed by the drive to obtain more substance.

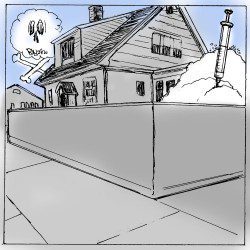

Yet others’ conflicts are also part of the problem. Such as well-intentioned family members who long for loved ones to get sober but later undermine their loved ones’ sobriety when abstinence reconfigures the distribution of power in the household. Or well-intentioned addiction treatment professionals and mutual-help members who are so attached to specific treatment approaches that they fail to engage newcomers who don’t align with them. Or well-intentioned community members who only support addiction treatment centers located someplace else, making treatment less accessible in their own neighborhoods.

Conflicts of interest often involve money. Do some doctors prescribe controlled substances too freely? Could some addiction treatment facilities provide less than rigorous care so that patients will return? Are some health insurance companies more invested in restricting access to care than providing it? Are some managed care reviewers rewarded when they deny coverage instead of certify it?

In order to be used, addictive substances must first be available. Use increases when these substances are easily obtained, which promotes new addiction along with recidivism among the abstinent. The business interests of large segments of the pharmaceutical, alcoholic beverage, tobacco, and legal marijuana industries are in conflict with the health interests of the public. Might the business interests that boost substance availability also influence decisions of government and other policymakers?

Besides availability, belief that the risk of harm is low or otherwise acceptable is a second condition to be met before many individuals will initiate use of addictive substances. Numerous people who subsequently developed addiction were given a false sense of security from well-intentioned peers, family members, healthcare providers, and the media including advertisers, reporters, and editors.

Respectful, nurturing interpersonal relationships in families and throughout society reduce the vulnerability of young people to addiction and make recovery more attainable for those seeking a way out. Yet people continue to depersonalize one another, reacting to stereotypes rather than appreciating individual human beings.

Addiction statistics are not likely to improve until we all identify and accept our own unavoidable share of responsibility for curbing the problem. Individuals seeking recovery are responsible for accepting support and changing elements of their lifestyle. Communities—meaning everyone, including law enforcement, business, government, healthcare providers, third party payers, and the media—are responsible for reducing the availability of addictive substances and permissive attitudes toward their use; making individualized addiction treatment accessible; reducing barriers to transportation, employment, and housing; and replacing stigma with respect.

A collective desire to be part of the solution may not be sufficient to make a difference. Healthy change proceeds more reliably when individuals are held accountable. For example, recovery from addiction often requires that family, professionals, and recovering peers keep tabs on those entering and maintaining recovery and impose consequences if they get off track. Likewise, we may all better meet our responsibilities if we gently but firmly hold one another accountable to act on addiction in ways that address the overall picture rather than just our own narrow point of view.

To think about: Will manufacturers and distributors of illegal addictive substances ever support the common good? Is accountability under the law the only possible incentive for them to change?