Welcome back to my blog. I appreciate your continued interest and I look forward to your comments. I have been quite busy lately and as a result I have not posted anything new for a month. One of the projects I have been involved with recently is related to a legislative meeting in Augusta, Maine.

I had the privilege to give testimony to the Maine Health and Human Services Committee this week pertaining to a bill sponsored by Senator David Woodsome (R-York).

I was extremely encouraged by the wide support the bill received. As you may know, Governor LePage (R), has emphasized increasing funds for law enforcement but not for treatment. We cannot arrest our way out of the heroin epidemic!

Here is the bill and Senator Woodsome’s comments, followed by my testimony. My testimony was coordinated with others, as we each had limited time to present. Collectively, however, we discussed all the important aspects.

LD 1473, “Resolve, To Increase Access to Opiate Addiction Treatment in Maine”

“Opioid addiction is a public health crisis in Maine. We need to approach the issue on all fronts, and that includes providing access to effective treatment. I have heard from many constituents in the Sanford area about those who have suffered because of the local methadone clinic that shuttered – we can make a difference in our addiction crisis and in people’s lives by funding treatment and clinics that are doing this work right.”

Testimony of Steven J. Kassels, MD

Medical Director, Community Substance Abuse Centers

January 28, 2016

Senator Brakey, Representative Gattine, and members of the Health and Human Services Committees, my name is Steven Kassels. I have been Board Certified in Addiction Medicine and Emergency Medicine. I have practiced medicine for approximately forty years and I currently serve as the Medical Director of Community Substance Abuse Centers which provides Methadone and Suboxone as part of comprehensive treatment programs for Opioid Use Disorders. I am here today to speak in support of LD 1473. I sincerely appreciate the opportunity to discuss the opioid epidemic with you.

Unfortunately, the disease of addiction continues to be a misunderstood illness and carries with it a significant amount of stigma, which is especially true of opiate dependency/addiction. When I give lectures and I ask folks to raise their hands if they know a heroin addict, very few hands are raised. But how can that be when we all acknowledge that we are in the midst of a heroin/opioid epidemic? I have treated college professors, school teachers, IRS agents, nurses, carpenters, electricians, politicians, homeless people and possibly your neighbors. We all know heroin/opioid addicts – we just may not know who they are. The stigma of the disease forces individuals to hide and to not seek treatment. This is a significant contributing factor why only one in seven people with the disease of addiction are in treatment. Today the highest increase of heroin users is comprised of white suburban men and women in their twenties and thirties. But why should this surprise us. In the early 1900’s the average opioid user was a middle aged, middle class, housewife and mother who typically was addicted to the opioid drug Laudanum.

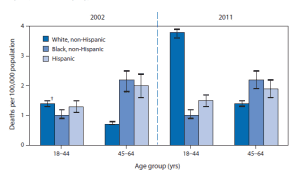

Heroin Addiction

CDC MMWR July 11, 2014

It is essential that we stop characterizing addictions into two categories: “Good” Addictions and “Bad” Addictions. Addiction is addiction, and whether we have dependency to alcohol or to heroin, the mechanism of action in the brain is similar. Both stimulate the reward center by eliciting their effects on the same area of the brain. In fact, the medication Naltrexone (“Vivitrol”; “Trexan”) decreases cravings for alcohol and also blocks the effects of heroin. Alcohol, heroin and cocaine all exhibit their effects by stimulating the pleasure center in the brain, the same center that gets stimulated when we eat a nice meal, go for a jog, watch a good movie or enjoy intimacy. With all of these activities our internal opioids, called endorphins, get secreted and stimulate the brain’s pleasure center. In fact, during child birth, increased secretion of endorphins are thought to help to diminish pain.

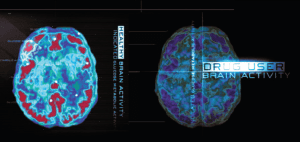

When a person uses opioids for a long period of time, there are changes in both the production of endorphins and its effect on the brain’s receptors. There are documented structural and functional changes that take place in the brain.

Brain Scan: Normal & Addicted Brain

“Drug addiction is a brain disease that can be treated.”

Nora D. Volkow, M.D., Director, National Institute on Drug Abuse

The question of whether these changes are reversible is dependent on the severity of the disease, no different than diabetes. With improved diet, weight loss and exercise, the pancreas of some patients will be able to produce sufficient amounts of insulin to no longer need insulin injections, while others will need insulin replacement therapy for life. Insulin replacement therapy in diabetes or steroid replacement therapy in the disease of the adrenal gland called Addison’s Disease is no different than endorphine replacement therapy. Treating patients with methadone or buprenorphine (“Suboxone”) is not replacing one drug with another; it is the use of a medication to replace what the body can no longer produce or use effectively.

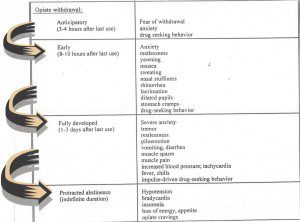

The changes in the brain in opioid addiction can be profound and can lead to a vicious cycle of severe withdrawal symptoms leading to drug seeking behavior and drug use to alleviate the symptoms, only to have the withdrawal symptoms return, leading to repetitive behavior. In the case of heroin, withdrawal symptoms start to return within 4-8 hours.

Opioid Withdrawal

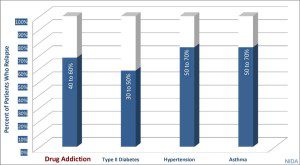

Opioid replacement medications interrupt this vicious cycle and decrease and eventually eliminate the cravings and drug seeking behavior. However, depending on the severity of the changes in the brain, some patients may need medication for prolonged periods. However, as in all chronic illnesses, success rates are not determined by “curing” the patient; but by limiting relapse rates and allowing the patient to resume a normal life. Furthermore, the relapse rates for a patient with addiction is not significantly different than those with other chronic illnesses.

Relapse Rates: Addiction & Other Chronic Illnesses

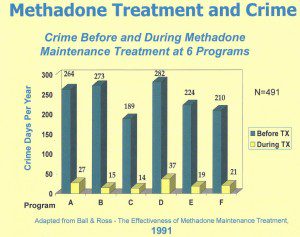

We do not arbitrarily limit type or duration of treatment for other chronic illnesses, so why should we for addiction? The key to success in treating opioid addiction is to eliminate withdrawal symptoms so the person can focus on a life free of drug seeking behavior, reestablish relationships and contribute to society. Maine statistics support this approach as do studies as far back as 1991.

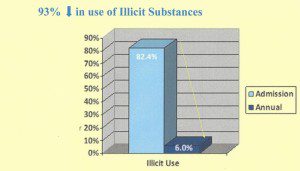

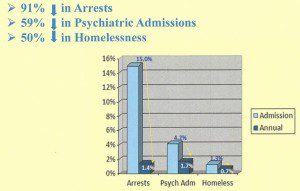

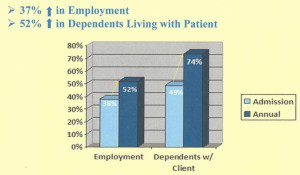

Information from Maine 2015 Treatment Data System

1991 Study: Effectiveness of Methadone Maintenance

The misunderstanding that the addict can be cured needs further explanation. We must understand that although it is a person’s choice to use a drug or to drink alcohol, it is not their choice to become dependent/addicted. Once addicted, similar to other chronic illnesses, there is no cure. When a person chooses to eat a poor diet, not exercise and becomes obese there is a greater likelihood they will develop diabetes. This is because the pancreas, the organ that makes insulin, has become injured. This change can be irreversible requiring the need for us to replace what the patient can no longer make, so we prescribe insulin. When President Kennedy developed Addison’s Disease as a result of his adrenal gland no longer being able to produce steroids, he received replacement therapy. The end organ that is diseased in opioid dependency/addiction is the brain. But this should not surprise us. The end organs in alcoholism is the brain and the liver. Nicotine’s end organ is the heart and lungs. Why is this relevant? Because when the opioid addict’s disease progresses from continued use, there are changes in the brain, which may become irreversible. However, “drug addiction is a brain disease that can be treated.”

Opioid replacement medications eliminate withdrawal symptoms and “normalize” brain activity. Methadone and Suboxone in therapeutic doses do not make addicts “high” and in fact block the effects of heroin and other opioids. But the essential key to success is regular counseling to ensure the patient gets the psychological and social support to integrate back into society in a productive manner. Replacement medication alone is not comprehensive treatment; counseling is essential and reestablishing the reimbursement rate to prior levels is necessary to be able to provide the necessary counseling to the patients. We must remember, that many of us live with chronic illnesses, but with appropriate treatment and support, there is a much greater likelihood of living a productive life. As a physician, I consider that to be success!